Mickey Hart, drummer for the Grateful Dead since 1967 in its many incarnations, should know a thing or two about percussion.

Now 65, he's participated in various projects at the Smithsonian Institution and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, among others, including studies in the role of music in healing and health. Hart's 1991 book, Planet Drum: A Celebration of Percussion and Rhythm, which he co-authored with Fredric Lieberman, is a wide-ranging survey of the big beat heard around the world and its place in history and culture.

Percussion is an old, old sound that goes way, way back: the big bang at the beginning of the universe is "beat one;" the rest, according to Joseph Campbell quoted here, is "a fragmentation in the field of time."

Long before rock'n'roll records were smashed and trashed because of their prinmitive beats, Buddhist monks coming into Tibet performed their religious practice without drums -- to distinguish themselves from the magicians and shamans of Bon, an older Tibetan religion and its drumming rituals given by the gods.

"Tsong Khapa asked Chumbu, 'Why do you use the drum? You know we don't use drums because that's the way of shamans.' Chumbu replied, 'I do it for Mahakala. He likes it.' Tsong Khapa was not convinced. He said, 'Try not using it for a while, and see if there's any difference. Personally, I think it's a superstition, and you don't really need it.' So Chumbu stopped using the damaru. But he felt unhappy and never saw a trace of Mahakala. Everybody was miserable. When Tsong Khapa returned he asked, 'Was there a difference?' Chumbu replied, 'There was a great difference! Mahakala didn't like it, and I don't like it. So, please, let's go back to using the drum again.' Tsong Khapa then reinstated the use of drums again in ritual."

It's myth-making on a grand scale, and stories like this run throughout Planet Drum's pages: the Buddhists learned to incorporate the power of rhythm (and symbolism) in the instrument called the damaru. The book quotes Buddhist teacher Tarthang Tulku:

"Buddhists don't get hung up on ancestral things. But an important reason we use bones -- human and animal -- in instruments such as the damaru, the thigh-bone trumpets, and in implements such as skull bowls, is to serve as continual reminders of impermanence and the immediacy of death. You know that death is close by, and death is an advisor. And you realize that your own bones will eventually be like this."

The full-page photo of "Priscilla," a 37-kiloton atomic bomb tested in 1957, brings home this point in an unexpected way.

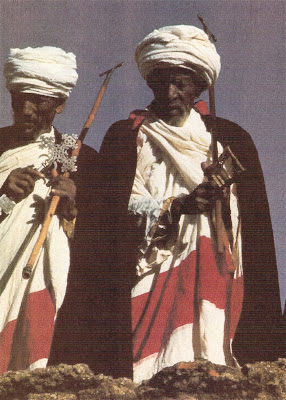

While including an atomic bomb may be a stretch, it emphasizes Hart's busman's holiday of drumming that takes on all forms in Planet Drum, from the Russian bell called Tsar-Kolokol ("emperor of bells") to the rattle of sistras in Eithopia. It's a big, sometimes dizzying tour, both in time and place.

The book is a museum of photographs -- a bit jumbled at times, with timelines and text splashed across the pages -- but the scope of the book underscores the universal uses of sound and rhythm throughout human history: from the beginning, a mother's heartbeat is the first rhythm we know. In life, in religion, and in war, the beat strengthens ritual, enhances enjoyment, inspires devotion or fear.

"Just what do we find so attractive about rhythmically-controlled noise? Part of the answer is found in the nature of percussive noise. Loud! Sudden! It trips the switches in the oldest part of the brain, the par

t that quickly reacts with a fight-or-flight program, stimulating the release of adrenaline ... we never feel so alive as when the adrenaline is flowing."

t that quickly reacts with a fight-or-flight program, stimulating the release of adrenaline ... we never feel so alive as when the adrenaline is flowing."Hart calls drumming "our musical skeleton key" -- an appropriate metaphor for someone still Grateful after all these years, in whatever shapes the Dead are still performing. It's almost April -- another spring season, with warm weather and green days ahead; time to celebrate renewal, rattle those pots and pans, time again to shake that old bag of bones. Twirling is optional.

(Images from Planet Drum, 1991)

1 comment:

This essay on "planet Drum" was so interesting to me; in fact I was overjoyed to read your thoughts and comments.

I had the cd from that time but did not know that it had been published as a book. I bought the cd as I became interested in "the drum" as a percussive/meditative tool. I began writing my own poetry around 1991. It was not great poetry (but I enjoyed it), and, so, Robert encouraged me to recite it aloud while beating my drum. What great fun we had. I did a performance piece at Cafe Diem with the drum and had a real good time.

I miss Robert so much. It is coming up on the 10th anniversary of his death. I sometimes feel I'm the only one that remembers. I welcome your writings on the importance of the consideration of death in our lives. Not too many people choose it as a topic of conversation. Thanks.

Post a Comment