After every holiday season the growing pile of books by my bedside keeps threatening to topple over one dark night and crush me. Until then I keep adding to it -- this Christmas even my landlord added to the weakening of my eyesight by presenting me Team of Rivals, 700 pages of Abraham Lincoln's politics and the friendships he nurtured into his tenure as President. Good timing for this political season and great stuff, even if I can only get through two pages at a time. That's okay: I like Doris Kearns Goodwin's near-obsession with the tandem story of Mary Todd Lincoln, and read those pages with even more attention.

Unfortunately this means that the list of books I promised myself to read, and some re-read, this year gets re-arranged. Great Expectations is there for a third reading. There's also an ultimate goal of a first-time through of the 800-page Bleak House (I swear it's in the bed-side pile). The first ten pages, all London smoke and fog, is Dickens writing for the sheer money value per-word, but it's an incredible promise of the novel's interior landscape.

2012 is the Dickens bicentennial and so that makes him a target for some well-meaning and even un-comprehending tributes, television presentations, and general rewriting of Dickens for this modern age. Britain, of course, is well ahead of the colonies on this: the BBC is already in full swing with new versions of Pip and Magwitch in the churchyard, as well as a presentation of Dickens at home in his serial of personal and financial troubles heartwarmingly titled Mrs. Dickens' Family Christmas.

In the Guardian UK, Howard Jacobson sounds a note of warning about the re-casting of Dickens' all-too-human stories for a "modern" audience in this celebration. He mentions one egregious example of the BBC embroidering the "meaning" of Dickens' fiction: Jacobson writes, in the context of one program, it should not have been necessary to wheel out "real" people – a real debtor, real lawyers – as though the wildness of Dickens's imagination has forever to be hauled back to what's recognisably ordinary.

With a typically Dickensian mode of overstatement beginning with his title, "Charles Dickens has been ruined by the BBC," Jacobson makes his case in the opening paragraph. Then he goes on to illustrate a few ways in which the BBC gets it wrong in trying to contemporize the writer. And certainly in the large part, he's right: taking out the humor makes the morality play of Dickens' fiction a difficult lesson to learn -- it's as if the humanity of the characters, already embedded in their very names, has been erased. Pretty dull stuff indeed.

You don't have to like Dickens. Literature is a house with many mansions. But if Dickens gets up your nose, as he clearly gets up the BBC's, the question has to be asked why you simply don't leave him alone.

... Not only on account of what he wrote, but on account of his bridging the chasm between the serious and the popular, I consider Dickens to be our finest writer after Shakespeare, an example and reproach to every too high-minded stylist and every too low-minded populariser who has come after him. David Copperfield, Little Dorrit, Our Mutual Friend – beat that for an achievement.

As for Great Expectations, it is up there for me with the world's greatest novels, not least as it vindicates plot as no other novel I can think of does, since what there is to find out is not coincidence or happenstance but the profoundest moral truth. Back, back we go in time and convolution, only to discover that the taint of crime and prison which Pip is desperate to escape is inescapable: not only is the idea of a "gentleman" built on sand, so is that idealisation of woman that was at the heart of Victorian romantic love.

Great Expectations, in short, is a more damning account of the mess Dickens himself had made of love than any denunciation on behalf of the outraged wives-club could ever be. Missing from the usual attack on Dickens's marital heartlessness is any comprehension of the tragedy of it for Mr as well as Mrs Dickens, the derangement he suffered contemplating his own weaknesses, and its significance for the murderous, self-punishing novels he began to write.

That Great Expectations achieves its seriousness of purpose by sometimes comic means, that the language bursts with life, that its gusto leaves you breathless and its shame makes the pages curl, that you are implicated in every act of physical and emotional cruelty to the point where you don't know who's the more guilty, you or Pip, you or Orlick, you or Magwitch, goes without saying if you are a reader of Dickens. But you would never have guessed any of these things from the BBC's adaptation. For this was Dickens with the laughter taken out.

Of course you can't dramatise a novel and keep everything. But to exclude, say, Miss Havisham clutching her heart and declaring "Broken!" or Joe giving Pip more gravy, for the sake of a brothel scene that would have made Dickens snort, is inexplicable, unless your aim is to write Dickens out of Dickens.

We must guess that the BBC is embarrassed by the eccentricity of the writing, the hyperbole of the characterisation, the wild marginalia, the lunatic flights of fancy – think of Pip embroidering what he saw at Miss Havisham's (four dogs fighting for veal cutlets out of a silver basket) – the fearless seriousness which will drop into bathos or magniloquence at any moment, confident it can recover itself and be the wiser for where it's been. Lacking confidence in anything but a judgmental monotone, this major BBC production didn't reinterpret Dickens, it eviscerated him.

What the age demands, the age must be given. The "snob's progress" version of Great Expectations – a simplistic, retributive "class" reading about a boy who scorns his origins – is now the common one. It suits our would-be egalitarian times. But Great Expectations is more a novel about eroticism than snobbery. In an extraordinary scene, also excised from the TV version, Pip awaits the arrival of Estella with a disordered agitation, stamping the prison dust off his feet, shaking it from his dress, exhaling it from his lungs. "So contaminated did I feel …" And there's the novel's subject.

The fastidious consciousness of blemish that disables a man from loving a woman as flesh and blood, that feeds an idealisation which ultimately damages those he loves, and desexualises him. And all along, Estella the remote and icy star is more mired in the dirt of humanity than he is. She marries Bentley Drummle who makes no such mistake about her nature and beats her. Mrs Joe craves the attention of the man who tries to kill her. Sexual violence stalks the novel, making a fool of dreamers.

How Dickens was able to lower himself into these black depths of the soul and still make us laugh is one of literature's great wonders. He took us where no other novelist ever has. You don't have to like him, but you're impoverished if you don't.

"One of literature's great wonders": making readers see the humanity even in the darkest depths is what makes Dickens worth reading (and re-reading) in the first place.

Dickens died in 1870 after an extended reading tour of America, where he was drawn for the sake of his finances. By accounts it was a successful visit, and a necessary one, as Dickens tried to earn a profit in America with no copyright protections of his wildly popular work. Somehow the 700 pages of Abraham and Mary Lincoln's life in the 1850s / 1860s seems an appropriate companion to Dickens in the bed-side stack. Lincoln's political and personal fortunes are a contemporary American shadow of Dickens' impossible stories -- the frontier lawyer and virtual unknown who, improbably, rises to the Presidency and cannily succeeds by keeping his rivals close at hand.

Even so, the violence stalks him; Lincoln even has a dream of a catafalque in the White House, and is informed by a guard that it is "The President." Lincoln's assassination is the end of some sort of unbelievable fiction, but the pathos of Lincoln's ultimate tragedy must have seemed too much even for a writer of Charles Dickens' imaginative gifts to imagine.

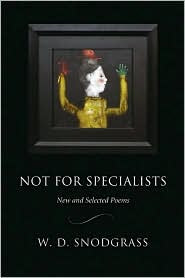

that the students in Winston are spoon-fed, much too comfortable, and more than a little vague. I have been known to be wrong...) The School of the Arts, Wake Forest, Reynolda House, and I spent $500 to bring him here; and Mr. Broughton travelled hundreds of miles for the occasion. The arts are a community and we owe each other attention, especially when we are as accomplished as JB.**

that the students in Winston are spoon-fed, much too comfortable, and more than a little vague. I have been known to be wrong...) The School of the Arts, Wake Forest, Reynolda House, and I spent $500 to bring him here; and Mr. Broughton travelled hundreds of miles for the occasion. The arts are a community and we owe each other attention, especially when we are as accomplished as JB.**